Bob Katz Interview, Part 2

This is the second and last part of our interview with Bob Katz — mastering engineer and educator in the field of high-quality audio. Read the first part here.

Bob Katz on Mastering for Streaming

We closed off the first part of this interview with a question on vinyl recordings and why they are still relevant today. Speaking of audio formats, has your work as a mastering engineer changed with the advancement of music streaming? Does a mastering engineer need to adapt in any way to the new methods of distributing and listening to music?

OK, no. I believe that for popular music — any kind of music that isn’t “classical” — hip-hop, rock, jazz — the dynamic range of a classic LP made, say, in the 70s and 80s is perfectly suitable for playback. At home, in the car, on streaming. You don’t have to compress it any more than that of a classic pop record from Simon and Garfunkel, Joan Baez to, you name it, any quality recording made in the 70s, 80s, or early 90s. So I have not had to adapt my mastering for streaming. I continue to make masters that have good dynamics, and an LP from the 70s and 80s has very good dynamics. Not extreme, but definitely impacting and not too little. So the answer to your question is that I haven’t had to adapt. And the clients are very happy with how it comes out in streaming.

Bob Katz on the Current Status of the Loudness War

Bob Katz on mastering for streaming.

What is the current status of the loudness war — is it over?

Apple has only turned on normalization by default on new devices. It will take a while before everyone has new devices. Spotify continues to retain the -14 LUFS target level, which generates a mini loudness war. Because some mastering engineers who would master at lower levels feel they should push their levels up to -14 LUFS. Spotify will not raise anything that started lower than -14, which is good because you don’t want it to overload, but at the same time, -14 is a little bit too loud for a lot of dynamic music. So Spotify’s target holds back a lot of dynamic productions — or potentially holds it back unless you have an artist who’s willing to tolerate that.

I’m gonna name Adele. I don’t know if she’s ignorant of the fact that her stuff sounds squashed. I can’t listen to her stuff. I love her performances — there we have an example of someone whose music I’d love to listen to, but I can’t. I feel the same way about some of Norah Jones’s releases. They sound a little too compressed for me. So is the loudness war continuing? To an extent, it is. It’s going to be a long, long time before every mixing engineer, mastering engineer, artist, and A&R realize that the more you raise your music’s average level, the more the platform will take it down. It’s going to take a while. So we need as much publicity about normalization as we can give. There’s already a lot of awareness of normalization, but there needs to be a lot more. So it’s going to be a while. There’s still a loudness war going. I’d like to think it’s a little less than it was five years ago, though.

Bob Katz on Mixing on Headphones

There seems to be a trend towards more and more mix engineers doing most of their work on headphones instead of spending most of their time on speakers and then doing a quick check on headphones. What do you think of that? Do you share this impression?

Yes. I think it’s very dangerous. I’ll go over some reasons why. First of all, headphones change the mix in terms of the instruments that are dominant will stay dominant, but instruments in the background sound clearer and more obvious on headphones. So when mix engineers check their mix on speakers, they’ll be disappointed that the clarity of their mix that they thought they had just isn’t working out. I don’t think that there are any successful tools that get around that issue because the headphones are so close to your ears that you can hear “everything”. That’s the insurmountable issue if you’re mixing in headphones. If you’re mastering and not trying to make mix decisions, that’s another question. But let’s go into areas where headphones could deceive a mastering engineer, not just a mixing engineer. The first thing is, I would say, separation. The stereo separation is tremendous in headphones because you have complete separation between the speaker elements. With speakers, the left speaker leaks into the right ear and vice versa, and your head causes time delays and shifts in frequency response which you don’t have on headphones. In addition, there’s a difference in transient response which I don’t think you can overcome either. When you have headphones on top of your head the level of transients is much higher than it would be with loudspeakers many feet away from the listener. I don’t think that’s something you can overcome completely with headphones, even with crossfeed circuits. But I am dabbling with crossfeed algorithms, and they are getting promising.

So the primary issues are separation and the direct to reverberant ratio. You feel, if you’re mixing, the direct to reverberant ratio is going to change in that you’re going to hear the inner details of the reverberation, but when you play it on loudspeakers the sound is going to be less impacting, softer, less detailed, and more diffuse. Since loudspeakers in a room will, so to speak, soften the presentation compared to headphones. So I don’t think you can make good reverb judgments when you’re on headphones.

When you’re mastering, however, maybe you’re not trying to decide how much reverb or ambience there should be in a recording. You’re just trying to make sure that, primarily, the tonality is working. There, we have a potential candidate that, in an emergency, a set of very good aligned headphones could work or even be used as a secondary reference.

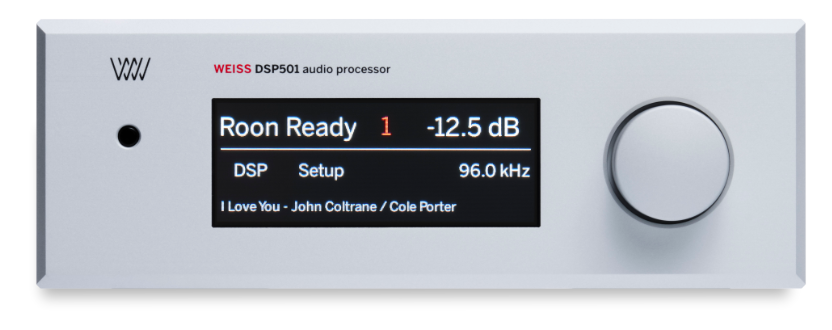

Bob Katz: is the loudness war over?

I actually have an experience with that. My mastering loudspeakers had a technical issue a while back, and for about four or five days when we were looking into the loudspeaker issue, I had to try to continue mastering. I have a pair of the Audeze CRBN electrostatic headphones. They are exceptional headphones — very, very, very pure sounding and extremely transparent. I do EQ them slightly with the EQ in the Weiss DSP501, I have developed an EQ setting for them. I tried to subjectively get the tonal response of the CRBNs to match up with the loudspeakers. You can’t do that by measurements. Because the headphones are on top of your ears and the speakers are many feet away from you in a mastering environment. As a result, you just have to go back and forth, back and forth, and subjectively try to match the curves until they come as close as possible.

So I had what I thought was a very successful EQ curve, and I had a couple of my close friends who are professional mastering and mixing engineers come over and contribute to the EQ curve as well. We thought that the CRBNs with Bob’s EQ on the Weiss DSP501 were very successful. Of course, you have to start with some extremely linear headphones to begin with, like the CRBNs. I used about five bands of very gentle EQ, nothing severe or sharp. I also used the crossfeed algorithm in the Weiss DSP501. The crossfeed plus the EQ I had developed allowed me to work on the CRBNs during this emergency period and do successful work. I was amazed! I took the masters I made and listened to them in my Studio B on my Kii Three loudspeakers, and was able to confirm the masters turned out well. I would give my usual caveat — don’t try this at home! My ego aside, I’m a very skilled mastering engineer, and I was able to master for a period with headphones, and a crosscheck on mastering-quality loudspeakers.

So to summarize, you wouldn’t recommend people to work in headphones as their main source for monitoring?

Not for mixing, even if you do a perfect EQ. But for mastering, in an emergency and with skill and the right tools, I believe it can be done.

Bob Katz’ on Loudspeaker Correction

What do you think of loudspeaker correction systems? Do you EQ your own monitoring?

I’d be very cautious about these pre-determined EQ correction curves. A lot of the units and applications over-compensate. I wonder about the aesthetic and musical listening skills of the people who have made these headphone compensation curves — if they have genuinely compared the EQ’ed phones with absolute flat-reference monitors in a good room.

With that said, I do use EQ on my monitoring and I’ll tell you a little bit about how I adjust the high-frequency response of my mastering monitors. You’ll see that it’s as objective as we can get — subjectively. Haha! First of all the speakers are adjusted very, very flat to start with. Flat using a great correction tool called Acourate with a convolver called Acourate Convolver. It has a special type of variable FFT window to compensate for the way the ear hears and a number of other things. So we start out flat. But as many people have discovered — flat does sound bright. Flat loudspeaker response sounds brighter than you’d think, for reasons I don’t have the time to go into. So then you have to decide how much high-frequency roll-off to apply to the speaker and at what frequency. That took quite a while for me to refine using about 50 reference recordings that I have used over the years continually, including references that I have mastered and other masters in many different genres. So I adjust the high-frequency curve of the loudspeakers until the middle of the references sound just right. And the bright ones of the references don’t sound too bright, and the dull ones don’t sound too dull. Once you have that, the high frequency response of the loudspeakers is as accurate as possible. I applied the same approach to the headphones. So if you have the experience and skills of knowing what’s a good reference, and have been studiously collecting high-quality recordings, then you have the tools to adjust the speaker frequency response.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Depending on the size of the room, the bass tends to be preferred a little bit up from flat. In my studio A, it’s 0.2 dB or 0.3 dB up from 125 Hz and down. In the smaller mix room, it’s almost 1 dB up.

All of that leads to the question — how do we beat the circle of confusion? Our recordings are made and adjusted using monitors that are adjusted using recordings that are made using monitors … etc. How do you know what’s correct?

Well, I believe that my method of using the 50 best reference recordings will create a loudspeaker EQ, at least in the bass and the treble, that will be correct and surpass the circle of confusion. Once you start with something that measures flat and concentrate on bass and treble shelving if necessary. Some loudspeaker experts may disagree with my approach, they have a right to because they’re experts in the field. But curves like the Bruel and Kjaer have been validated and around for decades. My curve greatly resembles B&K and is simply adapted to a particular room and loudspeakers. To repeat, I believe if you take as many high-quality reference recordings as possible, then the average of these recordings made over the years should fall right in the middle of your loudspeaker EQ. If the average of these reference recordings sound just right, then I believe you have surpassed the circle of confusion and ended up with a correct reference. By the law of averages.

With that, we conclude the long interview with Bob Katz. A heartfelt thank you to Bob for taking his time with this!

Related Weiss Products

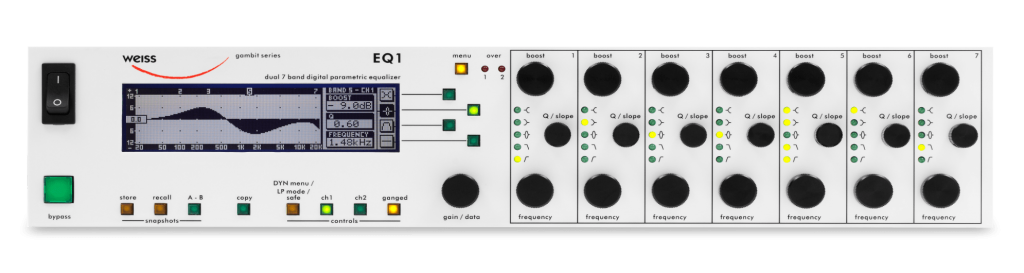

EQ1

“The sound is very, very good, lovely, warm, and beautiful, very analog-like. What more could one say?”

– Bob Katz

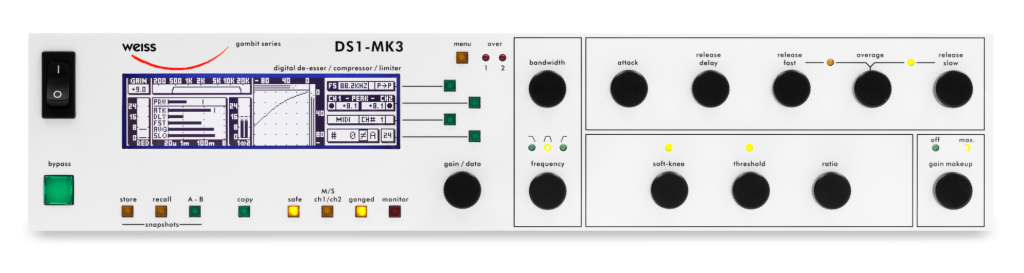

DS1-MK3

“The DS1-MK3 is the most transparent, refined, flexible, and least ‘digital sounding’ dynamics processor I have ever used.”

– Bob Katz