What is LUFS and how does it affect me?

Over the last few years, the term “LUFS” has been a big topic of discussion and a similarly big source of confusion, particularly among those who spend time mixing and mastering. We will make an attempt to sort things out. What is LUFS all about, what is the loudness war, and in what way do these things affect you as a mixing engineer, mastering engineer, and music listener?

What is loudness?

Everything in this article is about audio loudness, so we need to start off by understanding what the term means. One thing we don’t mean when we talk about loudness is sound volume coming out of speakers or headphones, the acoustic sound level you can — hopefully! — control with a volume knob. Instead, this is all about the loudness of recorded audio in relation to the capacity of the format in which that audio is being stored and played back.

Traditionally, there are two ways of measuring the amplitude of an audio signal — peak level and RMS. Peak level measures just that — the loudest peaks of the audio signal, or put differently, the maximum level the audio reaches across its duration. RMS, on the other hand, is a measure of the average level across the audio material’s duration.

Imagine two pieces of music, one with a reasonably constant level with few peaks and valleys and another that is quiet overall but has a few very strong peaks. The latter could very well have higher peak level readings, but the former would likely still be perceived as much louder, even with lower peak levels. Because when our ears and brains subjectively compare the loudness of two recordings, they tend to ignore short-term variations such as peaks and perceive material with a higher average level as being louder. So that’s the takeaway from this section — perceived loudness strongly relates to the average amplitude of the audio material.

We also need to get ever so slightly techy here. We mentioned above that when we talk about loudness, this is in relation to how much the audio format can carry. In the digital world, the maximum level the medium can carry without clipping (distorting) is denoted as 0 dBFS, decibels relative to full scale. So, if you think of a digital audio file as a box you can fill up to a certain level, that box is completely full at 0 dBFS. If you try stuffing more into it, the sides of the box will start cracking.

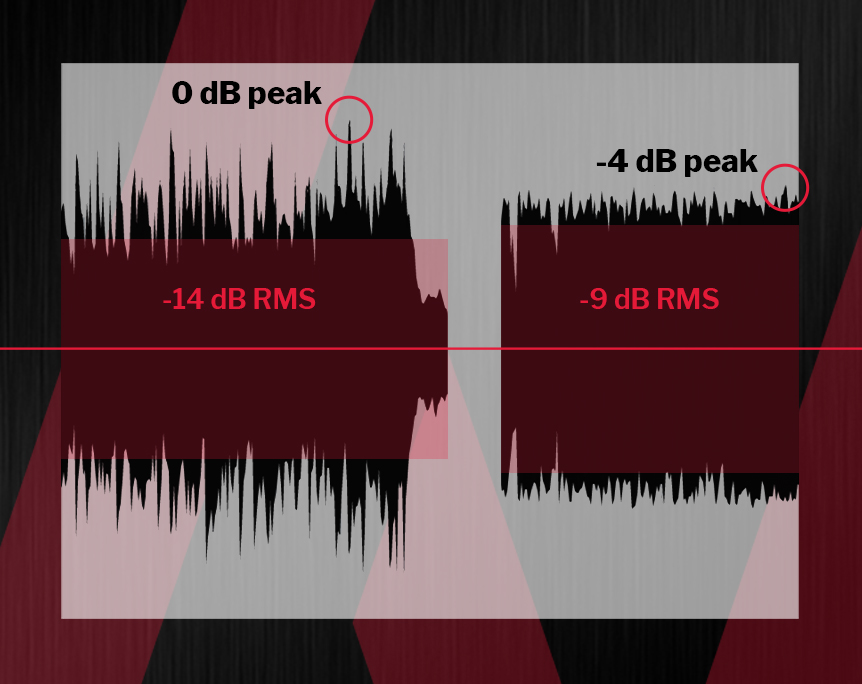

Two songs with very different loudness profiles. The left sound file has louder peaks than the one on the right. But the one on the right is more dense and has a higher average level. So even though its peaks are lower in level, it is perceived as being louder than the left.

Since 0 dBFS is the maximum usable level, all other relevant digital audio levels are expressed as negative values, such as – 8 dBFS peak level. That denotes an audio signal that is 8 decibels below clipping.

what is the loudness war?

The second part of the background we need to put in place before we get to LUFS is the loudness war. It was — I say “was” although it could be argued it’s not entirely over — a spiraling situation where mixing and mastering engineers competed by releasing music with increasingly high average audio levels. Everyone wanted their music to be perceived as louder than everyone else’s.

Why? Because if you play back a piece of music to someone and then play them the exact same music a tad louder and ask which one they prefer, the listener will prefer the louder one in about ten cases out of ten. If it’s just a subtle volume change, they might not even perceive it as louder, but the difference would be described as wider, deeper, and more engaging. Of course, all the record companies wanted their music to be perceived as more exciting than the competitors’ music. Therefore, they instructed mix and mastering engineers to make their music as loud as possible, and the war was on.

How does limiting raise audio levels?

But how does one raise the average audio level and achieve a loud recording? We just noted that the box that is digital audio can’t be filled over 0 dBFS before it starts cracking. One technique is to limit the peaks of the audio with a limiter. A limiter automatically turns down the peaks of the audio if they reach above a predetermined threshold level. Think of the standard graphic representation of audio, which looks like a Christmas tree the cat has knocked over on its side. The pointy branches sticking upwards and downwards represent the audio peaks (loud instantaneous events such as drum hits), and somewhere around the trunk of the sadly collapsed tree, you will find the average level. Now, the limiter can be used to reduce the audio’s peaks — cut down the branches of the Christmas tree. By reducing the peaks, you get them further away from the clipping level of 0 dBFS. With that in place, you can turn the average level up and still not cause digital clipping. As the average level is now higher, the music will be perceived as significantly louder than the original version and other music with a lower average level.

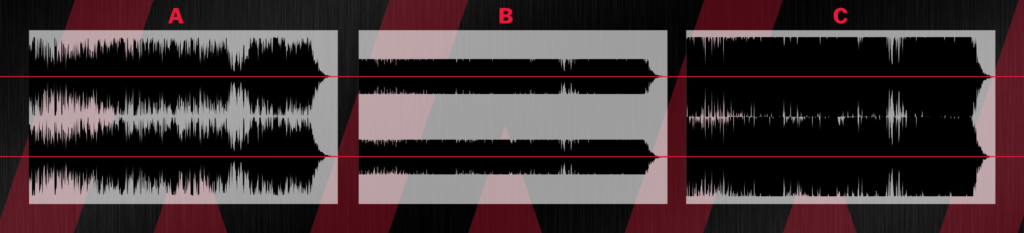

This is a somewhat exaggerated illustration of how loudness is achieved. All three sound files are the same song. A is the original file. B is the same file limited by 9 dB. In C, the limited version (B) has been raised by 9 dB, yielding a much louder result at the expense of a significantly reduced dynamic impact.

So, what’s the problem with that? Returning to the Christmas tree metaphor, excessively limiting music would be like cutting off the tree branches and inflating the trunk’s thickness to twice the size. A thick spruce trunk with its branches cut off is not going to make a particularly pretty Christmas tree, is it? Audio does not get particularly pretty when you subdue it with excessive limiting, either. Specifically, reducing the peaks makes the music sound flat and less engaging — dynamic contrasts get leveled out, which is fatiguing. It’s like turning a beautiful landscape with hills and valleys into a flat parking lot.

The other major technique employed to achieve loudness is cutting the low-end frequencies of the material. Bass takes up a lot of energy, so you can turn up the overall level more if you reduce it. All in all, the quest for loudness resulted in thin, two-dimensional recordings. One of the common examples of that is Red Hot Chili Pepper’s Californication. True enough, however esoteric the system you hear it on, the recording sounds like it’s being played back through a kitchen radio.

Apart from the music sounding worse than it could, the excessive limiting caused another problem for music listeners: there was no common standard and audio loudness levels were all over the place. Some records had much higher average loudness than others. If you played a record from the 1970s at a comfortable playback level and then switched over to a loudness war casualty from the early 2000s, the latter could be so much louder you would have to throw yourself at the volume knob to turn it down. That became an even bigger issue with the introduction of the DVD player, which can often double as a CD player too. Because of that, it became common for people to connect their DVD players to their music systems and have the sound from both films and music records come out of their hifi speakers. But film audio is significantly lower in level than records from the 2000s. Again, going from watching a movie on a comfortable listening level to putting on a CD resulted in more panicking jumps to reach the volume knob before the speakers blew up. TV commercials made matters worse, as makers of those also joined the loudness war. The idea was that having the commercial much louder than the movie people watched would capture the unsuspecting viewer’s attention more efficiently. More panic jumping at the volume control ensued.

This all became rather annoying, and the EBU (European Broadcasting Union) eventually decided to do something about it.

EBU R128

The EBU determined a new loudness standard that all European broadcasters agreed to adhere to, and broadcasters worldwide soon joined them. The new standard was called EBU R128, and we can all agree that they could have come up with a catchier name.

EBU R128 introduces a new audio level measurement called LUFS — loudness units relative to full scale. LUFS is a measurement that quite accurately describes how humans perceive the loudness of varying audio material. Ideally, any two audio recordings with the same LUFS reading should also be perceived to have the same loudness. Note that this has nothing to do with the listeners’ playback level, it’s only about loudness consistency between different pieces of audio. If one recording is played back at a comfortable level, that will remain the case if you switch to another recording of the same LUFS level. If one is barely audible, so will all others be, if one is earsplittingly loud, so will all others be — as long as the recordings are at the same LUFS level.

LUFS is based on RMS measurement, which we mentioned above. But LUFS has an added weighting factor, which takes into account that our ears and brains have varying sensitivity to different audio frequencies. Two audio recordings of the same RMS can be perceived as quite different in loudness. While LUFS is not perfect, it does a much better job than RMS metering at approximating how humans perceive loudness.

With LUFS in place, the second step was requiring that all broadcasters transmit audio at the same LUFS level — this is what is called loudness normalization. EBU R128 determines that standard to -23 dB LUFS. So whatever audio is being broadcast will have the same perceived level thanks to EBU R128.

Soon enough, the music streaming platforms also decided to implement loudness normalization. This is hardly surprising. The streaming format lends itself to creating playlists with songs from different artists in different eras, and having wild level changes between songs would be enormously annoying to the listener. Most music streaming platforms use -14 dB LUFS, with a -1 dB true peak safety margin to avoid clipping.

To understand what loudness normalization means in practice, let’s assume we have one record that has been limited hard to obtain a loudness level of -6 dB LUFS (which was not uncommon for an early 2000s record) and one that is 6 dB softer, so -12 dB LUFS. Back in the CD days, playing those back at equal volume settings on your stereo system would make the -6 dB LUFS record sound significantly louder.

Applying loudness normalization with the -14 dB LUFS standard, the -6 dB LUFS record will automatically be turned down by 8 dB, and the -12 dB LUFS record will be turned down by 2 dB before playback. Both recordings will now be played back at -14 dB LUFS, meaning they have equal perceived loudness levels. The listener can go back and forth between the two albums and enjoy the music without adjusting the playback volume.

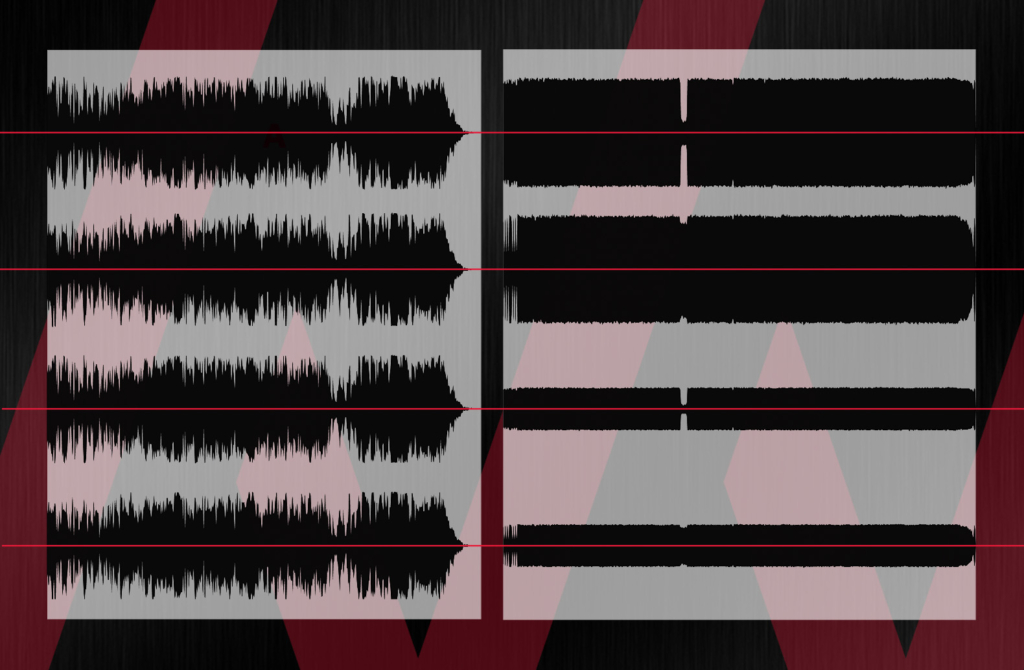

In the top row, we compare a Ray Charles song with a Metallica song. Both have been gain-adjusted to reach a true peak level of -1 dB. The Metallica track would sound significantly louder if these were played back at the same volume setting.

In the bottom row, we compare the same songs, but now they have been loudness normalized to -14 dB LUFS, as most streaming services do. These now play back at the same perceived loudness level, but the fact that the peaks in the Ray Charles song are so much higher than the Metallica song makes it come through as much more punchy, vibrant, and dynamic. Metallica sounds flat and two-dimensional in comparison, even though the tracks have the same perceived loudness.

What does this mean for mixing and mastering?

Good news! The other upside to today’s widespread use of loudness normalization is that mixing and mastering engineers no longer have to compete with loudness to the detriment of sound quality. The 13 decibels of available dynamics between -14 dB LUFS average and the -1 dB true peak is plenty for most pop, rock, hip-hop, etc, and does not require extensive limiting or cutting of bass frequencies. Many jazz and classical recordings have lower average levels, all the way down to -20 dB LUFS. This is because music in those genres often includes much bigger differences between the softest and the loudest parts. If the listener went back and forth between those genres and modern popular music, they would still have to make some adjustments to their volume to get the same perceived loudness. Because music with peaks at -1 dB but a softer than -14 dB LUFS average loudness will not get turned up on most platforms — if the recording is lower, it stays low.

This all means music creators now have much more liberty. If they prefer a more dynamic sound with deep full bass, they no longer have a disadvantage against loudness warriors and their thin, flat, but loud recordings. Those who prefer the sound of a hard limiter across their music can still apply that as much as they want. Nothing prevents that. The only thing that has changed is that they will now be doing it for the right reasons — they will be making an aesthetic choice to use limiting because they like that sound and feel it contributes to the music. Nobody can or should argue with their artistic choice.

Should I mix and master to -14 dB LUFS?

You should mix and master in a way that best serves the music. The loudness normalization of the listener’s streaming platform will take care of the playback level, so you don’t have to bother with that. Don’t overthink it. Instead, focus on creating the best sound you possibly can. If you like the sound of heavy limiting across your music, go right ahead. If you like it big and dynamic, go right ahead with that too. The only thing to be aware of is that if your track is very dynamic, with peaks reaching -1 dB and the average lower than -14 dB LUFS, your song will be played back at a correspondingly lower loudness level than most other songs on the streaming platform. This mostly applies to super-dynamic music such as audiophile jazz and classical recordings. The audience for such recordings likely prefers to adjust their playback volume if necessary, so again, we recommend that you mix and master in the way you think best serves the music and ignore other considerations.

After all, the aforementioned Red Hot Chili Peppers record was still a massive hit, with literally millions of records sold. So it would seem their listeners had no objections to the audio quality.